Beowulf: A Preview and Reading Schedule

Hwaet! A new season of APS Together

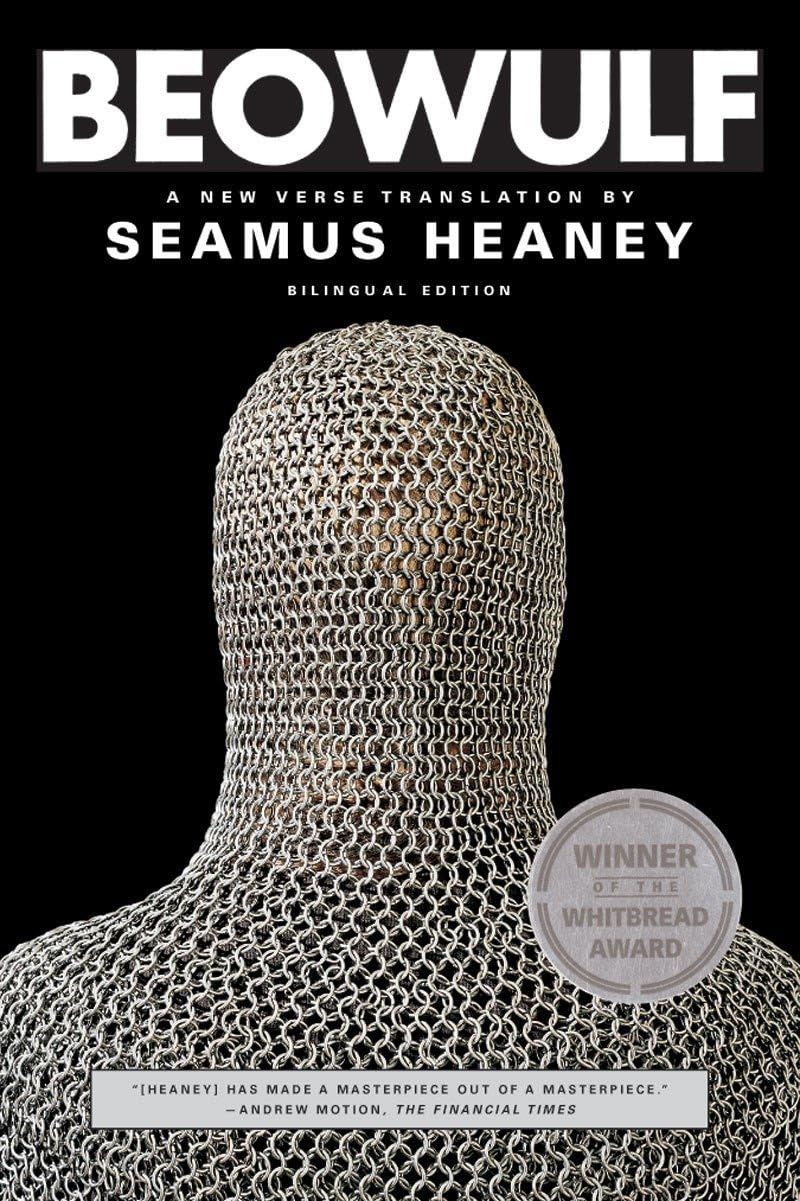

A new year! A new season of APS Together! Join us starting Tuesday, January 20 to read Seamus Heaney's translation from the Old English of the great epic Beowulf, together with longtime A Public Space friend and contributor Robert Sullivan. Hwaet! Off we go.

A Note From Robert Sullivan

The end of a year feels epic. So too the view from New Year’s Day to the months ahead. Is there a better time to turn to an ancient poem? To look back as we chart our courses forward, open new daybooks and behold as our Google calendars populate? In interviews and introductions, Seamus Heaney admitted a kind of regret in taking on the task of translating Beowulf, which, in the moment of his editors’ proposal, seemed doable, then, as one decade passed, then two, a hard row—“scriptorium slow,” he reported. Relief arrived when he saw a relationship between words in the poem and those in the land he grew up in; it was his key, a poetic security clearance. The gorgeously drawn, rhythmic lines that Heaney finally published at the opening of the twenty-first century feel as much like a poem as a vessel, a wave-carried craft with which we explore territories that are defined by uses, by strategies, by hopes and fear. See that advantageous prominence! Beware the moor swamped by dread in a landscape where threats deemed existential really are. Between kingdoms and seas, the destinies of individuals (“unknowable yet certain”) weave together like the gold-thread tapestries that fuel wars and warriors. Set your keel. Rig your mast with its sea-shawl and join us as we translate for ourselves an epic translation.

A Note on APS Together

APS Together is a communal-reading series from A Public Space. Join us to read together—daily, imaginatively, miscellaneously. Each session is hosted by a friend of A Public Space, who selects and introduces a book to read together; and shares notes every morning, with fellow readers joining in. At the end of each book, we gather (usually online) for a finale conversation with our APS Together host and A Public Space editor Brigid Hughes.

Reading Schedule

Day 1 (January 20): p. 1-11

Day 2 (January 21): p. 11-19

Day 3 (January 22): p. 21-29

Day 4 (January 23): p. 31-41

Day 5 (January 24): p. 41-48

Day 6 (January 25): p. 49-57

Day 7 (January 26): p. 59-69

Day 8 (January 27): p. 69-81

Day 9 (January 28): p. 83-91

Day 10 (January 29): p. 93-99

Day 11 (January 30): p. 101-111

Day 12 (January 31): p. 113-121

Day 13 (February 1): p. 123-133

Day 14 (February 2): p. 133-141

Day 15 (February 3): p. 142-151

Day 16 (February 4): p. 151-159

Day 17 (February 5): p. 159-171

Day 18 (February 6): p. 171-181

Day 19 (February 7): p. 181-191

Day 20 (February 8): p. 191-199

Day 21 (February 9): p. 201-213

Join us on Tuesday, February 10 at 7:00 pm (ET) for a finale conversation with Robert Sullivan and A Public Space editor Brigid Hughes.

Robert Sullivan is the author of eight books, including Double Exposure: Resurveying the West with Timothy O'Sullivan (FSG) and Rats (Bloomsbury). He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and an Arts and Letters Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013) was born in Northern Ireland. A poet, playwright, and translator, he received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past.” The Poems of Seamus Heaney, which collects poems from his twelve books in a single volume; The Translations of Seamus Heaney, which includes his translation of Beowulf along with other works and commentary; and The Letters of Seamus Heaney, which includes correspondence from public and private archives, are available from FSG. His poem “The Riverbank Field” appeared in A Public Space No. 12.

The Beowulf Poet wrote this epic sometime between the middle of the seventh and end of the tenth century in Old English. As Seamus Heaney notes in the introduction to his translation of Beowulf, “We know about the poem more or less by chance because it exists in one manuscript only. This unique copy (now in the British Library) barely survived a fire in the eighteenth century and was then transcribed and titled, retranscribed and edited, translated and adapted, interpreted and reinterpreted, until it has become canonical.”

over 40 years ago (ouch!), between my sophomore and junior year of college, I signed up for a summer class in Old English at Harvard Summer School. It was taught by the chairman of the English department (whose name is now lost to me) and I remember the privilege I experienced to be attending class with him in a spacious classroom in what may have been the faculty building in Harvard Yard. I recall wood paneling and lush carpet. I think class was held three times a week for the summer term. I still have our text book , "Brights Old English Grammar and Reader, Third Edition, by F. G. Cassidy and Richard Ringler" and I'll be keeping it close at hand. I had (just by accident really) studied German through high school (and for another year to fulfill my college language requirement) which made the Old English grammar much more accessible to me than it would have been otherwise. The following fall, I studied Beowulf (in Old English) in tutorial with the divine Ann Lauinger (now retired) at Sarah Lawrence. I cannot find my dog-eared paperback edition of the poem from that year, but I still have the paper I wrote for her. For those who want to join me in the weeds, there is a great online website that includes a recording in the original Old English. It sounds marvelous. https://ebeowulf.uky.edu/ebeo4.0/CD/main.html

Heaney's breakthrough about recognizing words from his own land in Beowulf is such a perfect example of how translation isnt just linguistic—its about finding the cultural frequency. That "poetic security clearence" phrase captures something real: you need permission from the text itself to enter it properly. I wonder how many translations fail because the translator never finds that homeground connection, just stays in the scriptorium grinding away at dictionaries.