The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni: Day 26

Chapter 20

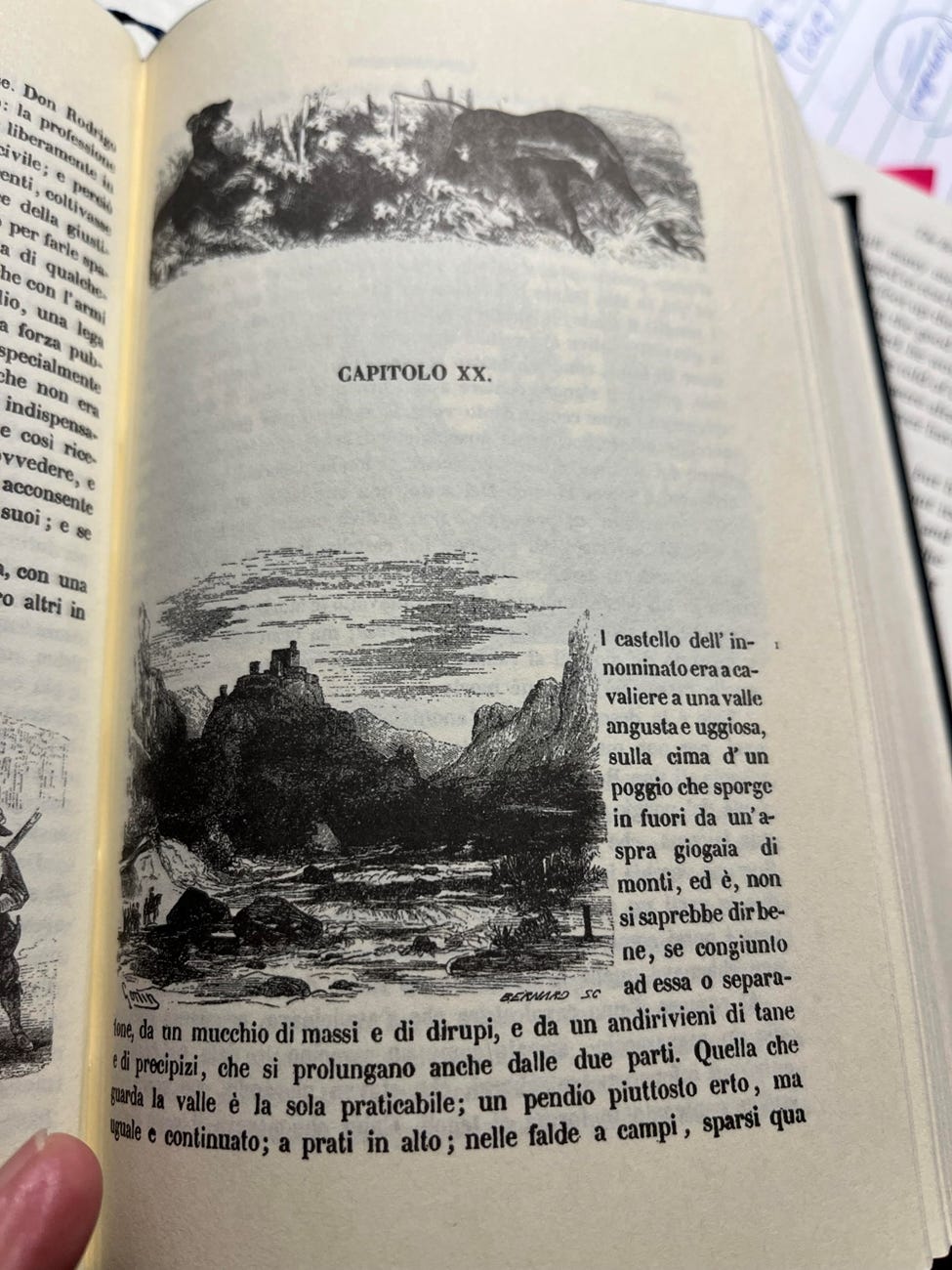

The opening to this chapter could have been written by the Gothic novelist Ann Radcliffe, whose The Mysteries of Udolfo (1794), as well as other works, was set in Italy, a country she had never visited.

“From the heights of his horrid castle, like the eagle in its gory nest, the savage lord dominated every inch of the area where a man might set foot.”

“The reader may remember that reprobate Egidio, who lived next to the convent where poor Lucia had taken refuge.”

Manzoni looping in that earlier chapter.

We are well down the path to iniquity here, yet there are glimmers of regret, of remorse, a festering sense of guilt.

The Nameless One suddenly fearing the Day of Judgment:

“Now, in moments of inexplicable despondency and unfounded terror, he imagined hearing His voice crying out from within: ‘YET I AM!’”

And Gertrude:

“To lose Lucia through no fault of her own, through an unforeseen accident, would have already felt like a misfortune, a bitter punishment. But now she was being ordered to deprive herself of the girl through treachery, to convert a means of atonement into a source of remorse.”

Here Manzoni wags his finger, but is the way of righteousness really open to her?

“My heart cannot bear to describe her ordeal any longer: An overwhelming sorrow makes me skip to the end of that journey, which lasted for more than four hours, after which we will still have some more agonizing hours to endure. Let us go now to the castle where the unhappy girl was being taken.”

I realize that some of you would appreciate a more detailed account, but perhaps our imaginations paint an even more lurid picture.

A final comment. I know that I should limit myself to three comments a day, but how can I ignore a gem like this:

“The idea of duty, which is deposited like a seed in the hearts of all men, had in her become associated with feelings of deference, terror, and an overweening desire to serve.”

Interesting to see the Unnamed and the servant women peeled open by the narrator, on the downside of their arcs of violence? “Still tormented by the need to boss someone around, and finding it intolerable to wait idly for the coach that was making its way to him too slowly, treacherously, almost punitively, he sent for an old servant woman.” Impatient, nasty, remorseful, worried, and bossy. (Bossy! The injection of a lighthearted word by Michael!) And the “old lady” after we are given her backstory with clear-eyed economy. “Prodded from her laziness and provoked into anger—her two dueling passions—she would sometimes return the compliment with words that Satan himself would have liked.” She is a piece of work.

I'm shocked at Gertrude's betrayal. Yet this chapter seems to be about the complexity and contradictions within human character and motives, invevitably defying the binary categorization of good or bad. Gertrude, the Nameless one and the "the old servant woman" in the Nameless One's castle all seem inwardly resisting against external forces that impel them to bad deeds. A part of each of them them has wanted and wants to be good.