Another odd, charged encounter between Eleanor and Theodora. We get a larger sense of Eleanor’s conflicted feelings about her appearance. Earlier, she was self-conscious about her hands, misshaped from years of household labor, but happy at the sight of her feet in red sandals. Now, when Theodora paints her toenails, she’s exquisitely sensitive to the “odd cold little touch of the brush,” but she responds to the bright red nail polish as though she’s been labeled with a scarlet A: “It’s horrible… it’s wicked.”

To Theodora’s query about why she doesn’t pay more attention to her appearance, Eleanor answers, “No time.” Again, this isn’t accurate: since her mother died, she’s been at loose ends, waiting for something to happen. She has time to do her nails! But psychologically, she’s stuck in the world of caring for her mother. “My mother would never let me get up and leave a table looking like this until morning,” she remarks after dinner. The housewifely mores of the 1950s, so often an undercurrent in Jackson’s work, show up even in Hill House. Those of you who have read “The Lottery” might remember that Tessie Hutchinson arrives in the village square with her hands still wet from doing the breakfast dishes: “Wouldn’t have me leave m’dishes in the sink, now, would you,” she says.

Beneath the surface, in both cases, I hear Jackson’s rage at the kinds of rules that kept women prisoners in their houses.

“I have a hunch that you ought to go home,” Theodora says after this exchange. It doesn’t take a clairvoyant to see there’s something a little off about Eleanor. Has Theodora picked up on the ways in which the house has begun to affect her? Or is what Theodora perceives as the house’s influence actually Eleanor’s innate self-consciousness and paranoia?

“I think that an atmosphere like this one can find out the flaws and faults and weaknesses in all of us, and break us apart in a matter of days,” the doctor says. Again, is he talking about the house? Or about the confluence of personalities in such proximity?

Only Jackson, who had a true horror of the dentist—see her story “The Tooth,” in the Lottery collection—would compare a haunted house to a dentist’s waiting room. This one’s online, if you have access to JSTOR through a library.

More adverbs: inadequately, gravely, stanchly, complacently, curiously, irrelevantly. This last one is a comment on the doctor’s query about who slept in the nursery. Is it irrelevant only because we know that it must have been the children who slept in the nursery? He “happily” takes measurements of the cold spot in the upstairs hallway, thrilled to have found a bona fide manifestation of the supernatural.

“‘Everything is worse,’ he said, looking at Eleanor, ‘if you think something is looking at you.’”

I find this line hilarious, but I’m struggling to explain why. Just the way it suggests the doctor’s cluelessness, I suppose.

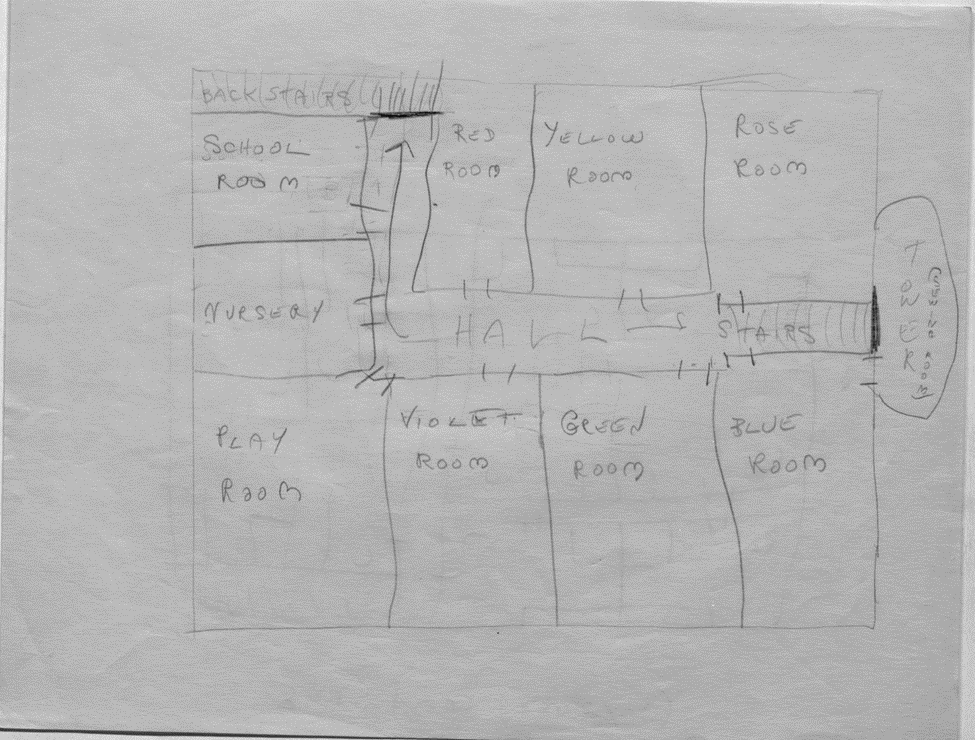

As promised, here’s Jackson’s drawing of the upstairs of Hill House.

I love this line, too: “‘Everything is worse,’ he said, looking at Eleanor, ‘if you think something is looking at you.’”

It's funny (the repetition of looking is amazing!), but it's also disturbing--the perfect Jackson combo. It reminds me of another favorite line, this one from Dickinson: "We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain." Always upsetting to feel the world looking at us with intention.

“Did you ever think about being homesick? If your home was Hill House would you be homesick for it? Did those two little girls cry for their dark, grim house when they were taken away?”

This exchange is creepy. Eleanor and Theo suddenly become the two young sisters stranded in Hill House, one eventually being jealous or suspicious of the other. I also am intrigued when Eleanor comments the doctor does not call Hill House by name.

These little repetitions, patterns, and comments either thought or spoken under the breath all seem to point to something, but like the characters’ uncertainty about the house, I’m not sure what any of it means yet, so I’m left feeling discomforted which seems the point.

Gothic horror, or any horror, is not a genre I’m typically drawn to, but I’m intrigued by how the external device of the house is drawing out the interior weaknesses or struggles of these characters. I’m also still wondering if Jackson worked heavily with outlines as she planned her stories and novels.